- Home

- Fernand Kolney

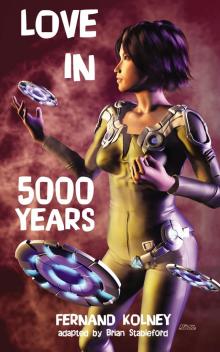

Love in 5000 Years Page 13

Love in 5000 Years Read online

Page 13

Moral refinement, alas, had not followed the same progression. The Family, the cell of the great social body, had remained intangible, and it still had marriage as a basis. Children, instead of bearing names chosen by the collective and being raised thereby, continued to bear their father’s name and to be his quasi-property—which slowly but surely reconstituted patrician families by virtue of the fact that sons inherited the status—which is to say, the title of official tribune, or chief of a district or other dignitary functions—of their fathers.

Many among the liquidators and sequestrators of the old capitalist Society had captured part of the money of the former possessors, in order to enjoy it later, when the time was right, for there is no known example of a political administrator who does not enrich himself.

At ever-closer intervals, briskly and punctually, famine depopulated entire territories. The whitening skeletons of cadavers littered the ground, for the arms of the survivors did not have strength enough to dig graves.

Sometimes, too, from time to time, insurrections burst forth. Those whom inanition had spared, weary of suffering, sharpened oak branches and hardened them with fire, and made flint axes as in the Stone Age, brandished agricultural tools and rose up to attack their persecutors—but the latter had maintained the art of war for themselves and their innumerable clients. Surrounded by the compact phalanx of their hirelings, they swept the “enemies of society” away with typhoons of fusillades and cyclones of machine-gun fire. And when the multitude had spilled the blood from its breasts and the brains from its skulls upon the quivering ground, they approached, laughing, as if to notify it that it is always face to the ground that one has to approach the great down here...

In the early months of 2160, however, everything changed. The Americans, a mixture of pietists and usurers, who had thus far refused to join the Occidental Federation, suddenly hurled their weapons and munitions against the old continent at full tilt. Boycotted in its commerce by the European bloc, afflicted in its living endeavors and quasi-moribund, America had decided on a desperate coup before resigning itself to disappearing from world trade. Its cargo-vessels disembarked savant strategists and improved artillery to arm the malcontents of European socialism.

Once again, the Great Work of Human Liberation was attempted. The new slaves of the socialist Salente32 recovered courage. Cleverly organized and commanded by generals from beyond the ocean, they gave voice to the preponderant speech of long-range weaponry. Prolonging the day and substituting for the sun, an aurora borealis of conflagrations hung the chandelier of a lustrous gala of carnage and universal destruction from the sky.

Divided into near-equivalent forces, the beneficiaries of the established order and their enemies caused a spreading tide of blood to run before them at every encounter. In the enormous cities, the prodigious capitals, the shards of houses, the roofs of palaces and the fragments of buildings flew away in swarms, borne by the deflagration of explosions, and to redden the clouds like a fabulous sunset, a pollen of human debris rose up, propelled by the formidable breath of panclastites.

The European civil war lasted for five years, and when the administrators had been exterminated, the dissidents of socialism introduced a considered sociological method. They put their generous victors to death on the very day of triumph. The Yankee tacticians were, therefore, shot without discussion and the general staffs annihilated to the last man without any hesitation or inefficiency, by way of comprehensive gratitude.

Then the “will to survive” and the illusion that flows therefrom—which is to say, the belief in the fatality of progress—immediately orientated the United States of Europe toward Neo-Malthusianism.

The convulsive disorder and iniquity of socialist organization appeared to them to be attributable to one principal factor: the pullulation of citizens, procreated bestially without taking any account of social necessities.

With that observation, a serene theory and the face of an apostle surged forth in a radiant dawn that slowly exhumed them from the background of the Past.

And in spite of many frustrations, disappointments and disasters, in spite of the fact that the route followed by civilizations is strewn with many pitfalls, from which groaning voices from beyond the grave of immolated people rise up; in spite of the fact that the brambles that hem its borders are still bloody from having raked the open wounds of Races; in spite of many resentments, panics and crucifixions, humans set out once again to launch into the future the pale doves of Hope.

The prophet who emerged thus from the heart of darkness was Paul Robin.33

With the face of an ascetic and the beard of an Islamic prophet, Paul Robin had been one of the sages of the Thébaïd of atheism and clear-sightedness, a thinker who dreamed, above all, of brining human societies into harmony with the plan of the World. Before him, two sons of women had opened intelligent eyes upon Life. The first, Pascal, had said:

“Imagine a large number of people in chains, all condemned to death, some of whom have their throats cut every day in front of the others; those who remain see their own condition in that of their peers, and look at one another in grief, without hope, awaiting their turn.”34

The second, Darwin, had studied it with a scientific brain and had brought its hidden mechanism into the light. Resuming the work of Lamarck, he had succeeded in validating the latter’s discoveries. He had imposed this evidence upon knowledge: that the contexture of the universe is completely different from that evoked by religions—and he could thus explain the creation of thinking beings other than by means of the absurdity of God.

Dissecting Nature, he showed that, having initially concealed the mystery of her modes of initial fabrication, and having permanently prevented the counterfeiting of her inventive methods, she safeguarded the duration of her work by assuring perpetuity thanks to the instinct of self-preservation and the instinct of reproduction, to which she provided the regulation of selection, the struggle of individuals for vital supremacy—which avoided excessive encumbrance and imposed equilibrium.

Only the permanence of life is important to her, and she demonstrates that cynically by the triumph of the fittest, by the systematic suppression of the weak, who can only create disorder and enervate the vigor of species. In that, she resembles the honest author, the conscientious stylist who, without weakness, destroys his imperfect productions.

To the sociologist and the philosopher, Darwin opened luminous and fecund paths. He permitted Paul Robin to give to human redemption the only logical basis that it ever had and ever could possess. To the metaphysician, to the sincere writer, to the seeker of the absolute, he granted a license to reflect the immorality and ferocity of the Great Active Force. To his commentators, he delegated the care of establishing that our sentimentality opposes itself to the rigor of Nature, that the latter goes directly toward her goal without embarrassing herself with pity—the very basis of our morality—and that it is therefore necessary for us to estrange her permanently, on pain of no longer being able to exist socially.

At the end of the nineteenth century, when it was easy to abuse people with the contortions and capers of the electoral platform, when the braying of the populace was unleashed collectively by the slightest promise of the politicians who had taken up the old farce of the Church and followed its example in offering guarantees that their dirty pockets contained the golden key of future happiness, Paul Robin had come to make the voice of superior comprehension heard. To the miracle of the multiplication of loaves, to the Fourierist Last Supper that the hypocrites of the Parliamentary freak-show offered to realize in les than three thousand years, if only the Plebeians would consent to give them their votes for another thirty centuries, he had replied by showing the effects and studying the causes of the organized chaos.

Every day, he went forth into the hysterical saraband that unfurled at his feet in the monstrous city, into the macabre round-dance that draw the lovers of glory, ambition and money around the Power, into the demonic bambou

la that caused the trinkets of crime to shake on the bellies of the adulated exactors, among the faces, splashed with wine, pus or blood of official Clodoches,35 in order to preach the truth, indefatigably, to offer the olive-branch of a better future. Greece would have counted him in the number of its seven sages, and Laprade,36 the last of the neo-Platonists, would have sung for him:

His disciples, draped in their woolen cloaks,

In myrtles and flowers grouped at random,

Received in their hearts, mute and breathless.

The balm that flowed from the old man’s lips.

And beneath the sarcasms, the clamors of ignorance, the vociferations of hatred, the gibes of ministerial prevaricators, the had retired to the Aventine Mount of the iniquitous capital to live there as a cenobite, nourished by the pure wheat of magnanimous ideas, drinking nothing but the hydromel of generous dreams.

But the day came when human beings finally perceived that their own interests and those of Nature are implacably antagonistic. The hour sounded when they understood that, by virtue of having proliferated without measure, and amusing themselves by proclaiming, to the extent of the extinction of all lyricism, the beauty and bounty of Isis, their pitiless enemy, they had not emerged from the cycle of barbarism, had not been able to do what, since their advent, the laborious ants and musical bees had achieved.

“Only the bees raise their offspring communally,” says the fourth Georgic. Children raised communally, with no privileges, that is definitive civilization. It was finally recognized that the maternal love that pours children into the mold of their parents’ stupidity, which hastens to revere the different sorts of cretinism in honor in the epoch, and the instinct of servitude inherent in any conglomerate of individuals, had been until then the two principal obstacles to the duration of the equitable City.

After the great upheaval of communism, Societies became perspicacious. All laws were abolished, and the superiority of one individual over another having been decreed to be abusive, humans no longer bent their knees or bowed their heads before their fellows.

In the wake of a reciprocal agreement, the Nations immersed in mid-Ocean, at a depth of four thousand feet, all the gold and metallic money—sources of so many crimes—that they had. Any citizen found guilty of having removed a part of it, however minimal, from the common destruction, was immediately punished by death, the agreed general interest. Soon, by the force of circumstance, as the possession of an effigy-embossed coin could no longer serve any purpose whatsoever, except to attract legitimate punishment the thieves destroyed what they had stolen of their own accord.

Then the Societies no longer had any but the children whose well-being they could ensure, whom they procreated prudently and selectively. A human race improved in intelligence and physique, exonerated, so far as possible, from ancestral flaws, took the place of the preceding one, engendered under the pressure of instinct, by the hazard of couplings and the supremacy of bestial drives. The Hellenic conception of Beauty was realized without further delay, thanks to the work of commentators on the Antiquity that, after having recovered the formula so many times, had finally had it accepted as the ideal. Youths clad in white wool were brought up at the expense of Just Communities, and in the palaestras, their foreheads circled by flowering reeds, threw the discus as in the time of Plato, coming thereafter to palpitate at the words of philosophers when the soft rays of the pacific star finally acclaimed the definitive triumph of Justice and Verity.

The era of the Phalansteries was imposed without hitches. In marble palaces edified with all that art had been able to arouse of esthetic marvels, the Ephemerals lived side by side, sitting down at abundant tables, to the sounds of harmonious music, listening to noble poems, informed by the masters of form and thought, savoring in all plentitude the delights of being perspicacious, free and just.

The great Aryan Family, so long divided, was finally reconciled. It had succeeded in sifting from human intelligence al the impurities with which inferior races had contaminated it. For two centuries, on that happy shore of the realized Ideal, the World enjoyed the Golden Age.

“Only two centuries?” one might say—but is not ten times twenty years of perfect happiness something miraculous, given the infirmity of the Universe?

Alas, human beings drag behind them such a mass of defects, turpitudes and villainies that the most patient moral surgeon could never have cured their soul. The alluvial deposits of rascality, the pestilential layers of mud that ineptitude, cruelty and the occlusion of preceding ages have heaped up their hearts will always overflow in the future to poison posterities. The heritage of frenzy, error and baseness is too heavy—as is the burden of unconsciousness and savagery, even on the shoulders of the Just, who feel their will weakening with every passing minute beneath the cope of maleficence that their “unconscious self”—their internal and vigilant enemy, perpetuated by atavism—places implacably upon their dolorous heads.

At that bifurcation of the history of Societies, the ancient Biblical theory of expiation appeared to be acceptable in its symbolism, provided that one eliminated the grotesque God who had ordered it, the God that the heart summons and reason rejects. At every minute in the course of the epochs produced by that lucidity, psychology, in accord with physiology and transformism, had verified it under the name of “heredity.” Undoubtedly, that sagacious sense of the immutable human condition, which could not free itself from primordial defect, must have been expressed for the first time by some Indian philosopher, perhaps contemporary with Confucius, and it had been adopted and subsequently deformed by the religious hysteria of the Jewish people.

At any rate, human beings have to expiate their irresponsibility, their reasoned ferocity, their initial error of orientation. And although there is no Will in the Beyond nor divine consciousness in the Present, their torment will only be complete with the End of Time. In the cage of the Great All, forever stuck in their evil instinct, are they not like flies struggling to escape from a glass bell-jar full of poisoned sugar and floating cadavers?

So, the abominable Judeo-Latin genius recommenced its deadly work.

Emerged from its filthy chrysalis, Evil, unfailing and patient, deployed its black wings once again, rattled its death-dealing wing-cases, and came to lay its eggs in the great social body. Immediately, the serene life that had swelled its arteries with a flood of health and juvenile delight, was afflicted by fever and sudden convulsions.

The Sages who kept watch paternally beside the bed of the libertarian Age, that last expedient of human hope, were soon anguished to observe the carbonaceous phlegmon, the color of a stormy sky, in which all the helminthes of decadence were already swarming. Vain were their efforts to release the poisoned anthrax, to extract the nucleus from the new worldwide abscess.

Crouching like a sphinx in the claws of nostalgia, at teats oozing torpor, Ennui brought its full weight down upon Libertarian Society, sterilizing its veins, gradually slowing its heart-beat in its already-anguished breast.

In fact, luxury was no longer the enjoyment of a few, but a delight savored in common; it required little labor to maintain and ensure its continuity. On the other hand two hours of daily labor were amply sufficient for the existence of Communities. Generalized, the indolence and sloth consequent on that state of affairs appeared in retrospect as patient gangrenes that had not been suspected.

People dragged their lack of occupation through endless days and yawned without restraint. Mouth open, they allowed themselves to fall on to the brocade couches of their palaces, marking with their collapse, the fall of noble poems or the finale of Wagnerian operas. The majority, to obviate the distress of doing nothing, “sought to occupy themselves,” as the common saying has it. Some sculpted chestnuts; others stitched walnut-shells. A few took census, patiently and scrupulously, of their neighbors’ hair, receiving the same service in return and thus calculating, every day, the disaster of the threat of baldness.

Physical culture being in great h

onor, they had repudiated the sports of the reproved Ages. At the beginning of every summer a sensational race was organized, a Tour de Paris, walking on the hands, for which the entries were counted in tens of thousands. Anyone who beat the record or palm-walking enjoyed a reputation that neither Stephenson nor Lavoisier had experienced.

Furthermore, the inherent vices of promiscuity reappeared. Coteries insisted on wearing their hair long when the majority favored a short crop—which led to the formation of a sort of council, which fixed, in order to confound the former, the dogma of short hair. Dandies, ambitious to stand out and thus escape social leveling, put their clothes on in a fashion contrary to regulation, and it was necessary to convene the assizes of Civilization in order to excommunicate the heterodox.

It often happened that an individual, by virtue of his imperious physique or skill in making sentimental speeches, reduced an entourage to voluntary servitude, which made him a sort of leader. On the other hand, in the public baths, a few individuals became suddenly famous for the caliber of their virility, and their numerous admirers demanded legal exceptions for them. As is evident, although it would have satisfied all the decrees that Greece had rendered in the name of beauty, the century threatened only to resemble the century of Pericles in its sodomy.

More seriously, the necessity of all working, of relaxing and of reproducing together, at times fixed in advance, led to numerous epidemics of suicide.

Love in 5000 Years

Love in 5000 Years