- Home

- Fernand Kolney

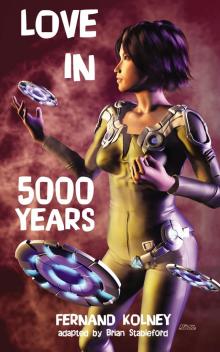

Love in 5000 Years Page 7

Love in 5000 Years Read online

Page 7

On his feather-bed, however, the Creator of Humans turned over and over in vain. Wrapped in his sheets of radiation, he could not attain the loss of consciousness, the febrifugal repose that would have applied a fresh dressing to his pained mind. An itch was burning his epidermis.

With his knees drawn up toward his chin, he surprised himself by mentally spelling out the syllables of felicity that formed Formosa’s name—and he sighed, propagating breezes that went to ripple the water in a nearby basin. For a second, his arms even embraced space, as if they wanted to take hold of an unreal but nevertheless graspable body. Then, having observed the inanity of is gesticulation, a reaction against himself and the other brought him upright.

He ran to a pill-dispenser, and swallowed two “benevolence pills” one after another—two granules of the solidified gas that he had devised—doubtless estimating that, in view of his pathological condition, the dose suspended in the atmosphere was insufficient to maintain at the supreme coefficient the sentiment of fraternity and affection for his fellows that he ought to be experiencing, just like any other Perfected.

His irascible effervescence declined, and he recovered a measure of order within himself, resolving to treat his delirium with the therapeutic effects of labor, immersing his thoughts in the vivifying bath of scientific speculation. He went into the study attached to the Fertilization Laboratory.

There, as everywhere in the Gem-City and the abode of the Sages, the walls were made of thick translucent glass. Sagax had placed himself within view of everyone, as everyone under his control was placed.

In the middle of the room, in fact, standing on a granite pedestal, was a marvelous optical and mechanical device. The apparatus had the form of a cube about half a meter square, and all the Phalansteries, all the transparent alveoli of the Perfected, were reflected therein, their images focused in perfectly clarity. A lens magnifying a hundredfold brought beings and objects to their normal size, allowing the embrace, in the slightest details, of the life of the immense hive, with its streets, its squares, its crossroads, thus permitting exact account to be taken of everyone’s position and activity.

The Grand Physiologist darted a paternal glance at the miraculous apparatus, and his chin dipped in a gesture of approval of the skill of his wise sons. The entire city was sleeping after the midday meal, taking a siesta after the ingestion of the concentrate tablets. He alone had not eaten and was thoughtful—but he did not feel any more appetite than he had an hour before, and, fearful that his illness might authorize some new absurdity, he plunged desperately into the jumble of his work.

His desk was covered with a multitude of drawings, illustrations and engravings representing the skulls that, in earlier centuries, had seemed abnormal to his forebears, and in a corner of the room there was a landslide of death’s-heads, a mound of occiputs, frontals and parietals, looming up like a tumulus.

A surprising event, of which Mathesis had given a hint during the Festivals of Life, had been realized. Coregium,18 the hero of the hour, had returned, two days before, from his adventurous expedition. Since earliest childhood, by means of rational education, he had trained his body to all exercises of strength, tempered his heart and hardened his nerves to confront all perils. Thus, he had succeeded where others had failed. The heroic enterprise that had previously been considered to be unachievable, he had brought to a successful conclusion: he had succeeded in plunging into the unknown of the World, which, around the last oasis in which Life had taken refuge, was no longer anything but a counterscarp of disorder, a rampart of chaos.

With a troop of determined companions, the bold fellow had marched toward the sunset. Mounted on automatic horses, whose unfailing mechanism could overcome any obstacle, the caravan had taken two years’ food supplies and a little apparatus linked to the machines of the City, which could thus furnish it, wherever it might be, with light to guide it, the warmth necessary to life and the motive force to search the terrains. All the expedition’s members had sheathed their bodies in coats of mail made of a metal as supple as the epidermis, which had the property of never cooling once it had been brought to a desired temperature.

For ten months they had wandered. A membrane of desolation lay upon the expanse where nothing and longer lived—neither plant, nor animal, nor insect. The Planet appeared there like an anatomical specimen conserved in the refrigerator of the eternal Winter. Almost everywhere, snow covered the ground like the close-copped fleece of an old man. The former relief of the globe had been blurred by the contraction of inferior crusts, and mountains four thousand feet high had collapsed into the plains, obstructing with their formidable barricades the routes along which the hope of Races had once passed.

Carried away by terror, the rivers had fled, like giant vipers, and Eumenidean tresses had thus come to coif the grimacing horizon. Monstrous avalanches overlapped, dressing the forested summits, launching frosty masts into the air, which impaled the low clouds as they passed, from which a deluge of hailstones then departed. Territories that ought to have contemplated the splendor of excessive civilizations, which the Sun still touches with its feeble rays, displayed a dust of cities, the ashes of capitals, as well as myriads of bones, which certain waters had petrified, myriads of skeletons, face down, with the head of the ulna drawn back against the rib-cage, resembling clouds of white locusts devouring, for want of anything better, the accursed soil.

The anguish of solitudes fell from the sky in heavy sheets and a glaucous daylight, a polar light, enshrouded Nature in the dusk of a renascent Limbo. A baldaquin of mourning and quasi-darkness was hooked on to the wan firmament, and a torpid silence was the jailer of entities overwhelmed by the breath of cataclysms.

An excursion of the little troop into the Far West had brought it, unexpectedly, into head-on collision with supreme terror. Out there, mystery defended its domain frenziedly, raising against anyone who attempter to violate it a right hand of madness—and it had been necessary to beat a retreat, almost at hazard, with horror-stricken eyes, shivering with fright, for the destruction was continuing their with method and virtuosity.

Coregium reported that the spheroid, returned to its glacial period, was convulsing in the movement of ice-sheets, in a tetanus whose spasms brought vagabond icebergs crashing together. The frozen oceans were sliding, racing to meet one another, uttering fratricidal clamors, attacking one another with spurs, throwing themselves forward fjords-first, and then, disemboweled, writhing in the throes of their tumultuous agony. The summits of the Alps, uprooted by the globe’s panic, were colliding, and sliding toward the western Atlantic. The profound vertebrae of the Earth were bursting like putrefied bones, projecting into the sky the shreds of muscles that were fragments of peninsulas, morsels of continents...

One evening, however, the pioneers had bivouacked on the site of a Metropolis they believed to be Paris, a fabulous city that, it was said, had long hypnotized the civilized world—and they had dug in the ground, laying bare the corners of unheard-of palaces and extraordinary monuments—an entire disconcerting sumptuousness. Risking a hundred times over being crushed by the jaws of oscillating vaults, they had ventured into the mingled entrails, the prestigious avenues, the labyrinth of magnificent streets, in a dust of glory that testified to the fact that they were finally in the presence of the Sovereign People.

Soon, to their great astonishment, they had discovered that the nation in question had spoken a language that was still that of the Perfected, and was then called “French.” Only one observation had thrown Coregium and his assistants slightly off-balance. Everywhere, at every step, a multitude of individuals stood up, for the most part hideous: statues perpetuating in bronze or marble the naïve awkwardness of their manners and the stupid pretentiousness of their persons. The explorer had thought that he was confronted by marionettes with which the jesting tribe commonly amused themselves, and which were represented on public highways to give younger generations a horror of the grotesque.

There was

one, above all, isolated in the middle of a vast square called the Place du Carrousel, who, bare-headed and clad in an unspeakable costume, was particularly clownish. His irritated index finger was summoning the distances to appear before him, for he seemed to be rendering them responsible for the theft of his hat and, from top to bottom of the stone bean-pole to which he was adjacent, his contemporaries, doubtless to avenge themselves, had engraved all the emphatic commonplaces that he had proffered in the course of his career.19

Elsewhere, immense monuments, exceptional palaces constructed with prodigious artistry, appeared to be the dwellings where these beings had lived in common, but little heaps of almost-impalpable ashes were all that remained of the citizens of that era, victims of the terrible Catastrophe.

According to a strange document, which related its history, that formidable city, which must have contained millions of inhabitants, no longer contained anything but “brothels,” a strange word whose meaning had not yet been elucidated. Once, the mortals who lived there had gradually lost their appetite for work, automatically dispossessed as they were of the fruits of their labor by men of prey called “speculators.” Gradually, the banks where the people operated who were known as “savings spongers” had chased the manual laborers from the factories, the intellectuals from the studios and the scientists from the laboratories. The masses had then developed a taste for “idleness” and “debauchery”—also words unknown to the Perfected. By virtue of progressive decline, this Paris had become the Whorehouse of the World, surviving entirely on traffic in flesh.

Strangely, everywhere and in myriads, the same two things were found.

Firstly, there was a book named “the Code,” which contained the rules that had administered the nation and listed the punishments that fell upon guilty parties of any kind. Secondly, there was a baroque item of porcelain furniture in the form of a broad-footed guitar.

Coregium and several of his companions, who had tried to read the collection of texts and formulas, had soon thrown it away, frightened, after having nearly lost their reason in the inextricable tangle of an infinity of laws, decrees, prohibitions, dispositions and quibbles reciprocally mixed in various doses to form juridical combinations more numerous than those regulating the different components of Matter.

The major part of that formalism came from a people nearly three thousand years anterior to the French of that epoch. Among the latter and for long centuries, the members of a special class spent the first half of their life learning and revering these text in order to have the right to violate them, during the second half, as functionaries of justice, otherwise known as “magistrates.”

Minute examination of the other object—which is to say, the quadruped violin—revealed that it was these recipients that the zoosperm cultures of their artificial fertilization laboratories were contained. That was indubitable, for a few desiccated spermatozoa had been discovered, stuck to the porcelain walls. Given the defectiveness of these utensils, however, and especially given that dust and air could penetrate them along with all the ferments they carried, there is every reason to believe that the generations obtained there from could not have been well-selected in physical and moral terms.20

Having encountered these two items everywhere, fraternally linked, and incessantly discovering them in excessive quantities, was it necessary to conclude that they synthesized the tastes of the Race, constituting the two poles of its aspirations?

Coregium had also been amazed to become entangled, every ten paces, in heaps of bewildering costumes, which all included narrow sheaths into which the arms and legs were inserted. The greater number of these garments were weighed down with braid, overladen with interlacings, embroidered with festoons and astragals, imbricated with silver or striped with gold. These wrappings had belonged to the chiefs of Phalansteries, and that love of disguise was another of the determinant characteristics of the population. No less absurd were head-dresses, cylindrical or marrow-shaped, which red chin-straps, embellished by a superfluity of ostrich-plumes or peacock-feathers, which were those of the Magnates of the socialist order. Engravings that revealed a means of finding pleasure whose secret has since been lost, merely by kissing the lips of women, were hanging from the walls in profusion.

Risking their life at every minute, only avoiding with great difficulty the collapses that threatened to bury them alive, the little cohort had succeeded in insinuating themselves, like a group of termites, into a gigantic building. It was the Library, the brain of that nation, in which, throughout the centuries, it had stored the treasures of its science and its genius. Having plunged into it boldly, they brought out an entire convoy of miraculous documents.

Furthermore, in a corner of a Museum adjacent to that caravanserai of books, they had suddenly stumbled, at the corner of a corridor, upon a heap of ridiculous skulls that were almost intact. At the sight of them, the astonishment of Coregium and his companions was such that they each leapt sideways, like a kangaroo that has just stepped on a thorn. In the disturbance of that common surprise, two of the explorers had even fallen, face forwards, on to the skulls, which had been dead for at least five thousand years, pulverizing several of them. Fortunately, eighty of them remained, which they had maintained in good condition by handling them with all the care due to their decrepitude.

It was those skulls that were heaped up in a white ossuary in the corner of Sagax’s study, and on which he was about to work. Scrupulously, he arranged them in parallel lines, ranking the by size as far as was possible. Afterwards, however, he was stupefied, and his larynx emitted a stifled double sound, “Oh! Oh!” proffered in the basso profundo of amazement.

He took a step back, as if in confusion, and came back, this time o articulate clearly: “The skulls of monsters!”

With disgust, and a tremor of revulsion for the past of fear and barbarism that it must represent, he took hold of one of them. Like the others, that one offered no similarity with those of current humankind. Confronted with the engravings, the drawings and the anatomical illustrations that represented a few teratological peculiarities observed in centuries already distant, he reestablished them by comparison. Undeniably, these skulls had belonged to an intermediate species, a link in the animal chain that led from the anthropoid to the human, for, by regression, the cephalic index took these subjects beyond the primates, into the ages of pure instinct.

Sagax bent down again, continuing his research. He collected on the floor ten of these containers of thought, which bore the most reprovable stigmata. Then he became ecstatic; his scientist’s soul savored the disconcerting anomaly in a pure gourmet spirit. Certainly, one could not classify them in the negroid type, the degree of relative perfection of those improved apes being still several stages removed. Their cervical capacity was, in fact, derisory, and their facial angle would have been repudiated by the hamadryad baboon or the howler monkey, fossils of which had been found the previous year. The lid where the hanging garden of the hair had once prospered was flat, the opposite of that of the present time, which was rounded out in a dome in order not to narrow down the gray matter that organized the carousels of Ideas. The bony cavity in which the great seats of Intelligence, the ardent chambers of Will and the parliaments of Circumspection had been lodged for Pithecanthropus, was swollen, inside, by spatulas and nodosities—and that demonstrated, undeniably, that their embryonic lucidity must have vacillated like a smoky candle in the frightful darkness of the abstract World, in the confusion of causes and effects.

The alveolus of the cerebellum, however, the seat of sensuality, was enormously developed. There were domiciled the nauseating abjections and anthropopithecine attractions that had not yet risen to a human level, an entire bestiality of unknown parentage. Anatomically, the fact could not be denied: for perhaps sixty years, the walls of that little locale had lovingly oozed shameless baseness and cynical turpitude.

Armed with a pair of compasses, Sagax recommenced the arrangement, and now, on the large table-top

, lined up the eighty skulls that paraded, artistically, in the virtuosity of incomparable malformations. In the middle of them, content with itself and disparaging its neighbors, was the king of horror.

That one, when alive, must have boasted a hypertrophic head, spongy parietals, the maxillaries of an alligator and the mouth of a shark. The top of the head unfurled roller-coasters under which a brain as large as a shelled walnut had danced. At the base, the sphenoid reared up seditiously, and the whole had undoubtedly surmounted a cetacean frame and paunch.

Pricked by the hundred needles of impatience, the Creator of Humans headed toward the iron chest and unlocked it carefully. Papers heaped in a compact wad, books of every size and pamphlets in every format appeared to him. And if one might put it thus, he received in his eyes a handful of the pepper of stupefaction, on observing that all these items were written in the same language that he spoke, as Coregium had affirmed.

Until then, he had not been able to believe it. The Perfected were, therefore, directly descended from the people that had caused such discouraging crania to appear. Gripped by vertigo, afflicted by a kind of frenzy, so great was his desire to know, that he abandoned the calmness necessary to scientific investigation. He plunged his arms into the parcel that still concealed the mystery of the past, took armfuls of documents, and threw them aside after having scanned them with an eye that raced through the lines, scarcely gathering any meaning therefrom. He thought for a moment that he had been misled; that language could not be his own—but no, there was no error!

Then, positively, he was afraid that he had fallen upon the monography of a house of raving lunatics.

With a vaporous dew oozing from his temples, his forehead, striped like a piece of sheet music with parallel wrinkles, and two parentheses beneath his nose, he launched himself in pursuit of the secret of the Ages, pursuing it in its ultimate retrenchments.

Love in 5000 Years

Love in 5000 Years