- Home

- Fernand Kolney

Love in 5000 Years Page 10

Love in 5000 Years Read online

Page 10

Immediately discharged from his responsibility, the Sage had no other recourse that to retire for life—and the sublime bottles gave birth to his successor, while one of his assistants assumed the Sacerdocy in his stead. Ten years, moreover, sufficed to bring an individual from birth to adulthood, for present-day Science, by means of special procedures, accelerated the work of Nature, causing the man to pass through the different phases of formation in a hundred and twenty months, thus shortening the long period of childhood and adolescence that previous Humankinds had known.

In the previous five hundred years, the Mechanical Criterion had only found someone wanting three times.

But what thunderous anathema was the inexorable apparatus about to bring down on Sagax’s head when he confronted it in his turn on the appointed date? Would he be able, on that day, to affirm to the People that all his thoughts had been devoted to the public good, directed to the meticulous accomplishment of the duties of his function? Would he be able to provide a guarantee that surprising aberrations similar to those of the aberrant trio had not come to solicit him?

“It’s a monomaniac who is in charge of the other three; to a cell with him too!” the multitude would howl, with every reason, and he would be doomed.

No, no. With all his might, it was necessary to expel the obsession whose tentacles were bruising his brain. His thought turned around; he descended into himself and took inventory of al his knowledge, which embraced the universality of things. Once again, he found nothing that could offer any similitude with the dementia that was presently given free rein.

Then he went back to the document brought back by Coregium. The same result: no case of abolished pathology could be compared with the present case.

Then, after a further desperate attempt, he was obliged to resign himself—but with what sadness, what disappointment, what self-disgust! A reaction of the human nervous system or brain had therefore escaped him, the Grand Physiologist! He was already insulting his genius when an elementary realization came to comfort him. Although, henceforth, it was not scientific to try to struggle against a disease whose cause and very nature he did not know, only being able to observe its effects, he had to be aware that, in the mental world as in the material world, there is nothing spontaneous. Everything is linked to something anterior, to seal the chain, to constitute the Great Cycle that is the Universe itself.

He had not gone far enough into the Past, that was all. Perhaps Antiquity had known disorders similar to those he could not yet identify. Had he not identified the monstrous skulls of the politicians? There was no doubt that, with a little more tenacity, he would be able, one day, to put a name to the epilepsy of the three subjects under observation. And again, he decided to pluck up his courage, to gather his critical faculties and launch his investigative spirit forward, to hollow out a mole-like path all the way to the putrid entrails of long-dead Epochs, in order finally to extract the truth from them, no matter what the cost.

His hand, plunging into the iron chest, came back this time with a volume bound in tan leather, and he was immediately enthused. The title, traced on the spine in letters that must once had been gilded but whose color had faded to a yellow-tinged gray, was only legible with great difficulty. It was volume III of a History of Societies, whose author was named Morosex.23

His heart gripped by the claws of anguish, the Creator of Humans hesitated to open it momentarily, for fear that nothing else legible would remain. The first pages were missing, probably having fallen into dust, and only one fragment of the preface—fifteen lines, to be exact—appeared at first. In three concise sentences, the author explained there why he had thought it appropriate to depart from the flat, colorless and circumspect style previously common to all Annalists.

To pillory the exactors, it said, to make their memory, that posthumous flesh sizzle in the boiling oil of molten lad of corrosive stigmata, ought to be the first rule of whoever devotes himself to resuscitate the defunct Ages. Only passion can restore life to accomplished Times, and it is making concession to rogues and rascals, encouraging the public malefactors of the present day, to record the crimes of those who have disappeared with the sentiment restraint and the moderation of epithets that has previously been applauded. That fashion permits the reader to believe that posterity can provide amnesty to crimes, that the passage of centuries effaces them in part, and that they have, at any rate, lost their importance in the eyes of the Chronicler, since the latter relates them at the tip of his pen with a schooled indignation that never upsets the beautiful equilibrium of his mind or his full stops.

The pages that followed were blackened, as if charred; in spite of all his precautions, they fell into ashes beneath Sagax’s fingers. He was already despairing when two chapters appeared, miraculously intact, with only a few passages destroyed. Avidly, he read them, moderating his exhalation, fearful that his breath might reduce them to dust. The Grand Procreator had fallen upon the Society of the twentieth century.

Stupid people! To maximize the shock and disgust of Posterities, when they were summoned to the bar in their turn, the Ruling Class had arrogated to itself the right of judging other classes; it had established a magistracy adequate to its needs. Recruited among the castrati of the licensed, selected with minute care from among the debris of its schools, sold in advance to the politicians who where masters of their careers, the bearers of the simarre,24 insulters of the poor, paladins of the rich, took prevarication and felony to a hitherto unknown degree of perfection. Without any other means of “succeeding” than displaying an exaggerated crawling, which incorporated their bellies to the floorboards at the mere appearance of the minister who issued the “Signature,” they sat cushioned in black lustrine, clad in a ruff of duplicity, an ermine of which the spittle of the crowd eventually ensured the whiteness. One single feature summarized that magistracy. For fifteen years, Courts and Tribunals gave a legal existence to fictitious individuals, offering guarantees of reality to the Crawford heirs that permitted the daughter-in-law of a Garde des Sceaux, their master, to steal forty millions...25

Having read this passage in Morosex’s history in one go, Sagax jumped as if he had jut been the victim of a powerful electric shock. His upper body abruptly extended the arc of his spine and threw his head backwards, his two eyes staring in amazement.

“What!” he cried. “They judged one another! They judged one another!”

And, his will giving notice to his nerves, he strove to recover a measure of self-control. As best he could, he clarified his mind, shook himself and snorted, not wanting to believe such a definitive abomination. Beneath his cranial cap, a disquieting stir filled his ears with a prolonged racket, for his civilized intelligence had just received such a jolt that he was physically pained by it. No, it was impossible! Surely he had gone astray!

He decided to do what he had never done before. He went to uncork a bottle, allowed a drop of the liquid it contained to fall on to a marble slab, and sniffed it avidly. It was Mensigene,26 which had the property of multiplying the cerebral faculties tenfold, without any subsequent depression, of stirring the intelligence, which then seized the best-concealed truths, projecting a kind of fulguration into understanding, which clarified the most rebellious darkness.

Until now, the Creator of Humans had been reluctant to employ that substance, developed not long ago, whose effect on the cerebral circumvolutions was not yet fully-understood. He had not dared to make use of it to analyze the disturbance that Formosa had fomented within him, for fear of being forced to recognize his own madness. He had wanted to avoid that formal diagnosis for as long as possible, which might not have left him any other way out than suicide.

Suddenly, he leapt across the study from left to right in a single bound, howling. What had he done? Oh, how right he had been, before, to mistrust the Mensigene! Had it not, with a sly caress, just reawakened the delirium that work had tempered? A knell was tolling in Sagax’s heart; a radiant form extended toward him, with dain

ty grace, the perfumed chains of its blonde tresses. Two breasts of marmoreal projection flourished in the chiaroscuro of his memory. Downy hips, satined with pink like the nacre of a sea-shell offered themselves to his hands, pricked by sudden burns. The sex, with its pleats of pink silk, surrounded by a necklace of golden moss, fascinated him as the eyes of a serpent fascinates a bird. At hazard, to drown his thoughts, to escape the maleficent obsession no matter what the cost, he precipitated himself toward his book and gripped it grimly, as his only instrument of salvation.

Suddenly, his hallucination dissipated; in his mind’s eye he saw the woman lean over the open volume, laughing, over the page that offered Knowledge, and suddenly flee with reproving gestures, as if she had just encountered the object of an innate detestation. Then he uttered a cry of joy; the luminous waves emitted by the Mensigene swept away the penumbra of the text, and the evidence appeared, triumphant, in its pure clarity.

He had not been mistaken! The people of the twentieth century had judged one another! Yes, those barbarians scarcely emerged from the limbo of Knowledge, those bipeds more ferocious than tigers, more serpentine than vipers, viler than insects that feed on faeces, those “civilized” people whose social edifice was aggregated with a cement of murder, a concrete armed by savagery, had instituted what they called “Justice” in order to acclaim crime on high and stigmatize it below. Those who could only prosper in their estate thanks to a domestication of every instant, those who, in order to rise in the hierarchy, had to manifest platitude and servility at every moment, all the failures of a Class that rejected with horror the truth science could bring them regarding the germination of truth in the human soul, were promoted to the dignity of “Magistrates,” and disposed of their fellows.

To legitimate that state of affairs, Morosex explained, these “civilized” people gave credence to the Free Will of which their religion provided a guarantee. Their superstition had installed in Space a Trinity of gods, a ménage à trois composed of a Father, an angry white-haired old man who spent his time spying on humans, a Daughter impregnated by the Abstract in order that her hymeneal membrane might be respected, and a Son born of the semen of a pigeon.

This trio set light to the suns, assumed the responsibility of policing Distances, relentlessly turned the handle of Gravitation, mended the holes in the Cosmos, patched up the Universe, polished the astral plane and passed a feather-duster over the Milky Way.

Following the example of these three Individuals, who presided over a Court of Assizes, working in shifts like the guards in a penitentiary set up in the Other World, humans, for more than twenty centuries, had therefore held one another to account and blamed one another reciprocally for their actions. Too ignorant to know that reactions of the muscles, excitations of the brain, modes of volition and states of thought are regulated by determinants that come from further away than the generation of an individual, and that the humans of the time, carried away by the conflict of causes and the eddies of mental effects, were no more responsible for their moral orientations than a molecule of liquid drawn toward a sewer or an unpolluted glacier, too obtuse to discover the fatality of determinism, those mammals undertook, by turns, the positions of judges or executioners. Their magistrates grazed, for ten years, the thistles of juridical rules, but had never attended the slightest lecture on psychology!

Abruptly, Sagax raised his arms above his head. Near to frenzy, evidently afflicted by contact with posterior Times, he hammered the floor with his heels, beside himself, and cried:

“There’s no doubt about it—in the atmosphere those long-dead monsters breathed there must have been an evil principle, an epilepsy-inducing gas that we have eliminated, and it’s necessary for me to rediscover it in order to explain the condition of the souls of those Unspeakables...”

Chapter VI

The Creator of Humans, powerless to stroll any longer in the tortuous labyrinths of antique aberration, had deserted his stacks of paper. He had not studied one per cent of the documents brought back by Coregium, and the latter was due to return before long to extraction from the Sources of the Past. But however impatient he was to know everything, he felt that he did not have the courage to swallow, at a single draught, that hemlock of desolation. He needed to get his breath back before remounting the hippogriff of the History that had flown him back to remote Times, when Peoples and Races had unfurled their fantasia of cruelty.

Besides which, Phegor and the alienated couple, still caged in their glass ergastules, could not be deprived of his care any longer. If it was impossible for him to cure them, at least he ought to continue his anterior medication and thus preserve them from definitive disaster. He therefore dispatched them his finest fluid, without the slightest confidence in its curative effect.

The crowd continued to block the Triumphal Way; curiosity, regarding such a persistent anomaly, was even greater than in the beginning. Treats were offered to the prisoners; people brought them flowers, as they did to pitiable invalids, and afflicted voices exhorted them to be patient, to persevere in the hope that Sagax would soon cure them. But the necessity was imposed of introducing public order measures—the first that the City had ever known.

With a common accord, it was agreed that one hour of the spectacle ought to sate the most demanding and thus permit all citizens to contemplate the three possessed individuals without risking excessive neck-strain.

The veneration of which the Creator of Humans as the object had, at the approach of his red toga, opened up the swarming crowd like some kind of plowshare. The furry humans who had, for the most part, been born via the intermediary of his bottles, greeted him as a father whose vigilant knowledge had, until now, freed them from dolor and affliction.

“Save them! Save, them, Sagax! They are your children too!”

The Grand Physiologist darted a glance over the isolation area, and a marmoreal pallor discolored his face. The condition of the plaintive three had worsened. For a second time, disappointment, mingled with anguish, seemed to close the valves of his heart, no longer permitting his arteries any but a parsimonious flow of blood. Thus confronting him, the Disease, increasingly mysterious, derided his genius—which, hitherto, had freed the human organism from all disorders! In the face of the Gem-City, it laughed at his vain strategy.

Sagax recoiled, crossed the street and backed up to the transparent wall of Phalanstery 134. The two lunatics had adopted an attitude of sovereign scorn toward the packed idlers. Lying on the mattress of radiations that raised them above the floor like a couch of ostentation, they smiled blissfully. Taking turns, they were seen to furbish their hands with the polish of kisses, and when the man, his temples circled by primroses, combed his companion’s hair with his fingers, the latter became delirious, her torso quivering, her fingers clenched, brushing her face with the man’s bristling beard while uttering little grunts of pleasure.

As for the monster, Phegor, the scandal of his ignominious gestures had been such that it was necessary to employ a previously unused coercion. Although the pride of the Neuters was to be naked, to have no garment other than their fleeces caressed by the breath of the artificial and perennial summer, Mathesis had made him a hastily-constructed pair of trousers. That garment, half red and half green, enclosed his legs narrowly, and the buttons that sealed the machicolations had been consolidated with brass wire. In addition, horsehair gloves with coarse and aggressive hair, which covered his hands, prevented him from harming himself. For the moment, squatting on is heels, he appeared to be meditating on the brief duration of human happiness, and an incessant repetitive moan emerged from his throat, which must have been the soothing complaint of his melancholy delirium.

Suddenly, his head began to shake, oscillating, doubtless an unsociable tic inflicted upon him by the excess of his depression. Then, one of his glances having picked out the Grand Procreator, he was seen to leap to his feet, with a mewl that made his co-detainees start. Amborix,27 the man with the garlanded forehead, immediately aba

ndoned the hair that he was raking delightedly, rounded his arm in a harmonious gesture, his lips anointed with affectation, and offered the gallant support of his arm to the woman.

Then, as if the presence of Sagax had hurled them beyond all restraint, they exasperated their sacred folly, all three sticking out their chests, threatening with their heads like bulls in a posture of attack, desirous of falling upon their tormentor. A forward bound brought them to the very edge of their cell, and although it had no wall facing the crowd, their surge was stopped dead by the omnipotence of the magnetic imperative, by the still all-powerful will that had kept them prisoner since the first moment of their incarceration. And the three bodies, launched toward vengeance, projected like blocks of stone by the ballista of fury, quivered momentarily, in suspense, and then fell down with a sound like rustling walnuts, sounding the knell of utter defeat with their sinciputs upon the sonorous tiles.

Terrified by this gesture of aggression, which the human species had forgotten forty centuries before, the faces of the crowd contracted in a unanimous rictus of horror. Faces became livid, wrinkling like those of old men. Was that singular madness about to restore to mankind the brutality and malevolence of immemorial Ages?

Fortunately, the comical aspect took over. A general burst of laughter stigmatized, as was appropriate, the childish presumption of the three deluded individuals who had tried to break their chains of suggestion, their hypnotic handcuffs, and to attack the head of the clinic who was trying to cure them. A second went by during which, undoubtedly, the incurability of the trio became manifest to the crowd, for the latter clamored, with the simultaneous explosion of its thousands of voices: “Give them a taste for death, Sagax! Infuse them with a desire for Oblivion, as you do for all the exhausted, for all those who, weary of life, come to ask our generosity for an appetite for silence, the blank ecstasy of supreme pacification.”

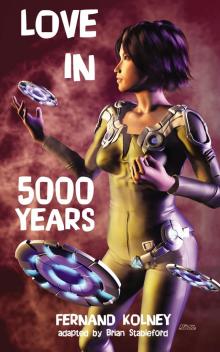

Love in 5000 Years

Love in 5000 Years