- Home

- Fernand Kolney

Love in 5000 Years Page 11

Love in 5000 Years Read online

Page 11

Sagax shivered, for he thought that he could rediscover in that cry the preexistent cruelty of human beings. In spite of all the cultures and all the selection, was that ferocity of distant epochs still in suspense in the Perfected individual? Or ought he to believe, less pessimistically, that the delirium of the three incarcerated individuals had aroused by radiation, that weakness of moral sensibility among the Neuters? The fact had never presented itself before, but henceforth, he would have to take it into account. Would his genius be powerful enough to purify the present zoosperms even further, and remove that final imperfection? As soon as he had triumphed over the present difficulties, he would have to devote himself to that task.

He did not think that he had the right to use the redoubtable power he had to overturn opinion, to transmute the value of things with regard to understanding, to turn around the human lens—in brief, to make someone who had previously cherished life with an unalloyed passion love death, when the person had not solicited it. That intrusion into the brain of another, which permitted him to insinuate therein the worship of and hunger for everything that had previously horrified it, to change its mode of feeling and reacting completely, he only permitted himself on the express requisition of his fellow.

Old men, more than two centuries old, had sometimes come to ask him to render the idea of death, which they wanted to anticipate out of disgust for their imminent decrepitude, delectable to their minds—and after mature examination, having retreated into himself, having analyzed everything, he had decided to modify, if one might put it thus, the gustatory sense of their mortality, to make death appear to them as an unprecedented inebriation.

With a gesture, he chased away the people who, at that moment, seemed to him to be comporting themselves like the vile human beings of old. And in order to make more certain of their flight, he threw into five thousand minds at once the idea of panic. A smile returned to his lips merely on seeing them gallop away, as if all the cavalry charges of ancient civilization were on their heels. Behind the multitude in disarray, Staroth, the cripple, inclined his spherical head and hopped after them, like a frog, on his bent legs, desperately striving not to lose contact.

Standing before the transparent cells, alone in the middle of the causeway, Sagax studied the monomaniacs. Amborix, the plantigrade with the forehead constellated by violet corollas, seemed to have accepted the disaster of his vengeance. Collapsed on the floor, he was licking his companion’s beast like a sorbet, only interrupting himself to plunge his face into the blonde tresses whose coarse golden mane pushed an odor of bitter honey into his nostrils. Phegor, the monster, rubbed the back of his neck and, with the greatest delicacy of touch, the thorny caresses of his hand scrupulously counted the projections of his occiput.

Sagax, on studying these contortions, understood that today, once again, there were no grounds for hope. He was about to turn on his heel, to retreat once again before the incoercible neurosis—for Amborix’s pantomime was giving him a stomach-ache, causing his saliva to dry up and beginning to draw a familiar form from the penumbra of his memory—when a sound like the muffled barking of a seal fortunately froze the name of Formosa, which he had begin to murmur, on his lips. Unexpectedly, Phegor, the unnatural product of bottle 1,324 seemed to pass the palm of his rugged glove over his epigastrum and then set about “playing the accordion” with a familiar disarticulation—which is to say, collapsing himself and then slowly getting up, distending himself tremulously, only to raise himself up again, rigid on his heels, vociferating the finest insults in his repertoire.

“You can well imagine,” he howled, “that I won’t spare my metaphors in revealing to you the only comportment appropriate to peel away the scales of dirt that are ringing on your epidermis of blossoming pedantry. You have only yourself to blame if you see me constrained to emerge from the perfect courtesy to which I’m accustomed in my writings and my relationships with my fellows.

“To gratify you with numerous taunts, as I was inclined to do just now, would be a consolation far below my just entitlements. The artificial, the simulated and the approximate, thanks to your jealous care, illustrate our epoch. You have vanquished Nature, it’s true; you have ripped from her womb that matrix of maleficence whose poisonous secretions ancient mortals lapped up greedily, but you have only thrown a canopy of ugliness, a black caparison of triumphant mediocrity, over life. Pasteur of zoosperms, Storer of human milk, Keyholder of omniscient stupidity, you are unworthy of that which you cannot comprehend and to brandish anathema over comportments above the vulgar...

“You have discrowned the world of the diadem seven times steeped in blood and tears that is called Beauty. Miraculous efflorescence! The milky sap of lilies of prepubertal candor, the somber genius of henbanes swaying athanors of insidious poisons, the sensual ardor of roses rubefying the light air with their red incandescence, and the horror of the artistic imagination, and the crime of confusing windfalls, and the semen of he-goats falling upon the flesh of virgins: all the charms and all the fears, all the languors and all the paroxysms—all that, you know, once ran in the veins of the Universe, giving it a soul, twisting it in the eternal spasm from which Life emerged!

“Before you, divine disorder reigned, administering the globe at the whim of its fantasy and prophetic strolling players, prose-mongers and poets with inspired lips drew the chariot of sacred art, went to plant the divine decors of Color, the Picturesque and the Unexpected everywhere. Your peers have assumed the will to bring everything down to the precise level of their baseness. Over the pollen of fervors and swoons blow by the breath of Azures, over the down of flowers that floated on the brow of Summers, you have evacuated the insipid odor of equations, the urine of theorems. Metaphysician of the Ridiculous, Philosophaster28 of the Grotesque, three thousand years of absurd sociology have made you sprinkle the earth with the cold humors of Banality!”

Short of breath, the monster could no longer play the accordion. His feet squared up, his body three-quarters turned, his right arm rounded like the handle of a basket, he seemed to be offering an illusory flower, the flower of his eloquence, at the tips of his fingers, held out like a rose-bowl.

Recovering his breath, he continued: “You forebears glorified themselves for having put a straitjacket over Tumult, for having vanquished Evil, the father of all renovation! Organizer of the almost, Superhuman of slovenliness, in what alcohol of stupidity have you pickled, like a grimacing fetus, what remains of Humankind, in order to offer it to the despair of future ages?

“Alas, humans have forgotten the magnanimous instruction of those who were the masters of joy and the educators of the mind, for what ever stupidity swells within your skull, you would not dare to describe as poets guttersnipes like Carminus, who goes so far as to be ignorant that the first duty of the self-respecting artist is to make mores appear above the common run that Athenians once taught.

“The bewitching charm of things and the duty to be beautiful no longer have disciples. Ugliness is henceforth the sole midwife of the mind; and in the stricken sky, in one final frisson, the twilight of all aristocracy, of all comprehension and all modesty. Wretch! What good is a victory over Dolor if you make us winter in atony? To suffer, perhaps, you hear, but to enjoy, to vibrate, to palpitate! Ah! Give my speech a persuasion so powerful that it will tear my vile neighbor away from his filthy pleasures—and both of us, then, will strangle you with our vengeful hands; yes, exterminate you, dried-up Nurse of impotence, annihilate forever the cold breath of your utilitarian dogmas, which have ventilated the world and given the sun a chill!”

And in an unconscious frenzy, he strangled the void with his hair-gloved fingers, sketching pitiless choke-holds in the air.

A gentle and comforting hilarity blossomed in Sagax. The depression that had weighed upon his shoulders a little while before had disappeared of its own accord. He found himself confronted by a case of reasoning madness—but a disorder that aroused the wheezy thunder of such abuse was evidently reduc

ible only by desperate therapeutics. From what he knew about anterior ages, he recognized therein the three dominant motifs of mental alienation, the three tangential points that it has in common with genius—which is to say, a need for didacticism, proselytism and invective. The madman, in fact, finds it necessary for him to explain his madness, and to recruit on its behalf, by glorifying it to others.

Without a doubt, the other two had only escaped that defect temporarily, but it seemed inevitable that its release in them would be manifest before long. As any dementia is a refuge into which the possessed locks himself, they had obtained no relief from the oratory manifestations of their co-detainee; for a quarter of an hour, at least, they had been persistently taking inventory of their intimate perfumes, which sometimes made them raise their heads to the skies, exposing their throats.

The Creator of Humans could no longer hesitate. He was driven to excessive means. His decision was made: the next day, he would subject all three of them to lethargy for half a year. That would permit to patient cure of their brains, striking their nervous centers with inertia, and by that very means—depriving them of sensory aliments—killing the “intrusive” inanition that was ruling them abusively.

Before turning his back on that lazar-house, however, Sagax gathered his will-power and propelled an unexpected suggestion toward Phegor. By virtue of a kind of paradox, he amused himself by investing him with that which, in his eyes, constituted the supreme human failure; he gratified him with what defunct civilizations called Faith.

Incontinently, the monster in the pillory turned round, bewildered, and fell to his knees with a movement so abrupt that his breeches ripped at knee-height. Bruising himself with his right fist, which beat his chest like a plaintive gong, he cried:

“The inelegance, baseness and ugliness of imbecile vegetables, among whom I strolled in the seasons of my youth, have infused me with the vehement desire never again to be ardent for anything but you, just and bountiful God.

“Once, I covered your learned intercessors with opprobrium; I splashed your altars with the juice of my scatology; I slapped your face with the dirty dressings of my ulcers and my infirmity. Huguenot, I reproached your vicars, whose shoes stink, for the fetidity of their breath, their horror of ablutions and the lack of charm in their profile. To the symphonies of your Levites, the unpolluted hymns of your virgins, I replied in counterpoint, with the avid mouth of the pamphlet. And I went forth, drunk with pride, in the cloud of incense evaporated by the feet of my companions, while the populace, with mushroom teeth, strangled acclamations.

“For twenty years, when your son displayed violet lips and his wounds, I defied him pugilistically, punching him with my epigrams and crowning him with my anathemas, in order to merit the votes of bad men. But he was beautiful! While I came to blows with him, my sacrilegious fingernails lacerated the bath-towel that was his only garment, and all his splendor, all his nudity, all his adorable flesh appeared to me. Weary, here I am, smitten by the blade of eternal passion, and I want to palpitate with him beneath the curtains of azure, in the sheets of Infinity.

“You know, redoubtable and indulgent God, that fervent flames have transverberated my heart, and I know longer have any desire but to shine, with my lips, the incorruptible Body to which Your Justice has given birth!”

The day before, one of Coregium’s documents had revealed to Sagax the mysterious source from which Phegor, the adulterated product of bottle 1,324, had come. The monster descended in a direct line from a protestant invert writer who had flourished around the year 1920.29 That Huguenot of the public urinals, afflicted with a blemish in the left eye and whose vice would have made his master Calvin’s eyes burst with horror, had attempted to give morality and a metaphysics to what was then called “pederasty.” After having sodomized Colas’ cow,30 now he was proposing to take Jesus from behind...

In order that his gaze should no longer be soiled by the sight of that ultimate degradation, Sagax out his toga over his eyes, and drew away at a slow pace.

Chapter VII

For three days, Sagax had shut himself up once again in his study deciding to confine himself in the strictest reclusion until he had finally torn the mask of mystery from the wrinkled face of past Ages. Devoted to that scrupulous investigation, he had sworn not to return to active life until he had exhumed, from the silt of five thousand years, the fossil of previous Humankind—in brief, all that remained of his science and civilization. In the chest that contained the redoubtable florescence of the Unknown, the documents appeared to have been squeezed by a hydraulic press, and he could only extract anything from them—exfoliate them, so to speak—with great difficulty, as one extracts from a slate the thin sheets composing it.

The conclusion of Morosex’s history seemed to have been lost, for, far from discovering the following volume, he fell upon a piece that had no relationship with it: a fragment of a much earlier novel or short story, devoid of a signature—a text that nevertheless furnished a few interesting details about Paris in the twentieth century.

He had read through it once, launching his gaze through its pages at a gallop, and he was returning now to a closer examination, a more profound study that soon brought him into contact with a number of terms, incidents and facts whose intelligence was refused to him. Certainly, he must have been confronted by some sort of sniping satirist who, in jest, by means of the artifice of humor and apparent paradox, was raising aspects of mores in forceful relief, giving the stupidity and turpitude of his era an unusual light, and them amusing himself by inducing them, melodiously, to bray like a donkey.

Monsieur Eliphas’ Promenades

A celebrated chronicler buried his unnatural life in order to marry the daughter of a compost king, and he had invited to the feast a large number of friends whose morals were of the purest Theban orthodoxy. The Huguenot of the urinals was to preside over this banquet and, his temples circled with phallic flowers, to quote Greek texts, when the delectable moment came in which the sodomites agglutinated.

The barrack-room was large, and before each napkin, each menu on which garlands of Priapus ran over the textured paper, shone a name famous in letters, the magistracy or the clergy. Fifteen splendid tziganes, fifteen human animals of incomparable form, fidgeted impatiently in their scarlet dolmans, and were to be delivered to the guests at the end of the meal. Spines braced, clean-shaven and sticking out their chests beneath their violet uniforms, their beauty and mettle made that feast the equal of the most famous banquets of the Palatine. A few guests having come to cast a glance into the hall, the fifteen musicantis uttered a welcoming whinny in unison, and beneath the moustaches of Hospodars, widely-flared nostrils breathed crackling fire...

The master of the house, as you can imagine, was complimented. But when, in the prelude to the orgy, everyone took their places, faces paled and there was general consternation. Disaster. The tziganes were no longer pawing the ground, much less sticking out their chests. Their spines, distended and limper than wet string, bent like the branches of weeping willows, and in the excess of their exhaustion, the lacquer moustaches were sweeping the tablecloth or dipping into the mustard-pots.

Who was the wretched author of the catastrophe? All the guests were accusing one another.

“It was him...”

“No, it was Monsieur.”

“I tell you it was Luluce.

“And I affirm that it was Carmen.”

They were about to come to blows. The defenders of Luluce, a President of the Court, being more numerous than those of Carmen, the curé of one of our basilicas, it was a good bet that the Church would once again suffer the insults of the century. Fortunately, there was a brief truce, called in a timely manner by the Huguenot of public conveniences, who, with honeyed words and cadenced gestures, made an appeal for concord, and, in spite of everything, opened the banquet by quoting fine authors. He recited from memory the anathema launched by Tibullus at venal chatterboxes in the fourth Elegy:

�

�Heu male nunc artes miseras haec saecula tractant!

“Jam tener assuevit munera velle puer,

“At tibi, qui Venerem docuisti vendere primus.

“Quisquis es, infelix urgeat ossa lapis.”31

Suddenly, the ambiguous son of Apollo uttered a howl in tremolo. Abruptly interrupted, he was grabbed, seized by the collar by his two neighbors, who forced him to his feet in spite of his resistance.

“He can no longer deny it, the rascal. He came in here before is and dried them all up…what a blackguard!”

And the two judiciaries called attention to the androgyne’s garments, whose disarray and stains testified to the misdeed.

“Fifteen?” I queried.

“It’s reasonable,” replied the celebrated chronicler.

“My head, my head!” moaned Sagax, who had just quit his stool. And he strode back and forth furiously. A drop of Mensigene, feverishly aspired, permitted him nevertheless to retain the certainty once again of the identity of the turpitude of the man with the blemish obstructing the left eye: the Polyphemus of the Urinals, as Mathesis had called him, and the monstrous geniture of bottle 1,324. But if the mistake could not be imputed to him, Sagax, how had it been produced? And how had “neuters” been able, in the year 1920, to realize such obscenities?

Sagax attacked another documents. From that one, it resulted that:

Firstly, in the Societies of the twentieth century, certain people possessed more than what was necessary to life; they called that luxury. By the same token, without any protest from the Masters of the Hour or the Masters of Conscience, they condemned to famine a large number of their brothers. However monstrous these certainties might be, one was forced to bow down before them. Thus, the words “rich” and “poor” were to be understood. Whoever possessed large quantities of a metal that had no other quality than not being oxidized, succeeded, by means of the inexplicable virtue of that elementary substance, in making his fellows work for his profit, and enjoyed, incontestable, a right to idleness and imbecility.

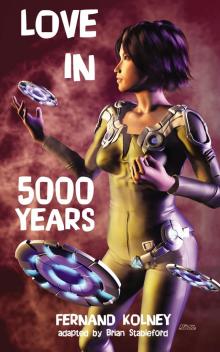

Love in 5000 Years

Love in 5000 Years