- Home

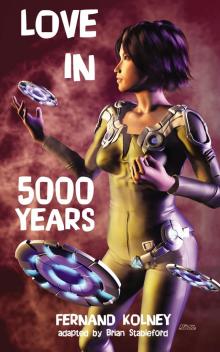

- Fernand Kolney

Love in 5000 Years Page 2

Love in 5000 Years Read online

Page 2

The language of the novel is so exotic that many of my other translations of particular terms might be equally challengeable, but I have done my best to reproduce its remarkable eccentricity. I have not bothered to footnote most of my Anglicized versions of exotic and improvised terms employed by the author, but have commented on one or two of the more potentially-controversial decisions as well as including the customary elaborations of historical and scientific references that no longer seems as transparent as they might have done in 1908 or 1928.

As with many gallica texts, the text of L’Amour dans 5000 ans lacks two pages, and I am greatly indebted to Frédéric Jaccaud, the curator of the Maison d’Ailleurs in Yverdon, for kindly scanning the missing text for me, from what was presumably once Pierre Versins’ own copy. As that copy too is the 1928 edition, Versins must have seen the footnote giving the original date of publication as 1908, and it therefore seems likely that the date of 1905 recorded for the original in his Encyclopédie is merely a misprint.

Brian Stableford

LOVE IN FIVE THOUSAND YEARS

To the memory

of my master,

the immortal Swift,

who informed me about

the satire of ideas,

this book is dedicated.

F.K.

Preface

In this novel I have posed the question of human happiness, the superior Civilization and integral Justice. Even by realizing that which we presently call the Absolute, can Science lead us to that haven of destiny of which all the prophets of every school and credo have already sounded the depths and delimited the shores? The moral dissection of the human heart, the impartial study of that ensemble of phenomena, which creates, although it is itself occasioned by a cause that escapes us, and the analysis—to the extent that it has been attempted—of the innate impulsion of matter, the attractive, radiant and co-ordinative magnetism that resembles a Will, and which one is obliged to call Nature, does not permit me to hope so.

May I be permitted an arid but short discussion? The present positivist philosophers who proclaim the fatality of the moral progress of humankind are nothing else, in sum, than misguided and unconscious spiritualists. They have replaced a bountiful and just Spirit with a bountiful and just Nature. They proclaim and glorify it, as believers proclaim and glorify their God; and by the same token, they have abdicated any critical intelligence or spirit of examination. If they were observant, they would son perceive that Nature proceeds in a straight line toward a defined goal, which is the perpetuation of species, that it crushes everything that opposes it in that work, that it is sovereignly unjust, that it recognizes nothing but force, and that its end is contrary to the interests of human beings, who can never impose upon it their sublime but utopian conception of equilibrium and equity.

These pseudo-thinkers have simply moved the principle of Harmony down a step. Instead of calling it God they call it Matter or Nature, but it is the same Moloch, the same unsated carnivore that is the object of their canticles of enthusiasm. Among litterateurs, see Rousseau and, at lower level, Zola.

Until Lamarck, the veritable world had remained hidden from the eyes of Humankind. After Darwin, who Perfected his work, a philosophy emerged to put the speculations of morality in accord with the reality of natural facts—hence the abominable philosophy, the Nietzschean morality, which tends to legitimate the right of the “fittest,” the “best adapted,” and strives to equip every socialized being with the maw of a shark. Thus, with Nietzsche, the bankruptcy and impotence of materialism is confirmed, an unfaltering ethics is fomented. In what will it be necessary to believe henceforth? In nothing. For what will it be necessary to hope? Nothing. In fact, is not deluded humankind, a hundred times deceived by all religions, now being asked by social or philosophical ideals for an act of faith as ridiculous as the preceding ones? Is not the fetishism of nature as ludicrous as the fetishism of divinity and revelation?

Alas, human beings can only live their lives precariously, in disorder and dolor, until the ineluctable hour sounds, in suspense in future centuries, that will lead to their disappearance, as earthly cataclysms have already led to the disappearance of so many animal species, to such profound scientific astonishment.

To scrutinize the Void, to furnish it, no matter what the cost, to deform at leisure the understanding of the weak, has been the work of the mythologies, ideologies and mystagogies with which libraries have been encumbered for the last three thousand years. Can one imagine that the human mind will ever find its foundations of serenity in any one of those pitiless folios of casuistry, scholasticism or metaphysics?

Everything is irredeemably bad, and the Future can only be woven on the weft of maleficence on which the Past was woven; that is the truth. The only wisdom that remains to us is to welcome the nihilism of the philosophical order, which incites the total suppression and destruction of the moral chaos in which we are struggling, by determined extinction and inertia.

No longer believe, no longer hope for anything other than implicit unhappiness during the duration of this brief accident that is Life. Any Science of happiness must, on the contrary, flow from the nihilism that, alone, procures for human beings the fortunate ataraxia of intelligence, in possession, this time, of definite certainties, at the same time as it frees sensuality from the rules of obsolete morality that have, until now, been able to rein it in.

All the inept conventions, all the stupid formulas, all the abstract links, including the “categorical imperative” itself, must fall before long, and are falling, before modern human beings’ tendency toward the maximum expansion of their individuality, before human beings selected by neo-Malthusianism, who will ultimately hold Civilization and the Universe to account for the atrocious condition imparted to them. They know, or will know, that accepted morality is merely a yoke designed to bow the head of the timorous and maintain the world in narrow servitude, to the profit of the privileged and cynical rulers, themselves free of any scruple. On the fragmented raft of the Ideal, they have the indisputable right to slake their thirst in all the saving rains that pour forth from skies momentarily opened by the largesse of Felicity. They have the right to sate themselves with all the joy that Life allows them to obtain; and the Censor that commands them to refrain is like the captain of a doomed galleon commanding his shipwreck victims to respect the ship’s stores and perish of starvation before the food-supplies.

Thus, nihilism does not hesitate to proclaim, loudly, that humans have no duties, save for those deliberated and accepted in advance, since, as Lucretius says, they did not ask to be born, but have submitted to the violence of being engendered.

That principal of finality has inspired this book, which, like its predecessors, breaks with the old formulae—which is to say, with the psychological or sentimental novel, attempting a diversion toward the novel of ideas. Its method is simple; it consists of not limiting the field of criticism, and also of reacting, so far as the author’s feeble means permit, against the hatred of style that characterizes the contemporary novel and causes almost all authors to declare in their prefaces that they are consequently using a “sober form” devoid of “vain ornamentation,” without “seeking images” and without unnecessary recourse to the unexpected and the fantastic”—which is the equivalent of saying that they will avoid literature as if it were a shameful canker. As can be observed, that procedure is not without skill, for it permits all geldings to pass themselves off as stallions. Indeed, is there any more practical means for them to explain the total absence of invention, the picturesque and color, rare qualities that identify the real artist, than by declaring those gifts void in advance and repudiating them as indecent?

As everyone knows, the three schools of Romanticism, Naturalism and Symbolism, which have maintained the boutique of masterpieces for the last fifty years, have, each in turn, put the key under the door. The art of writing is, therefore, presently pregnant with a new mode, and the birth is presenting difficulties,

as the critics affirm. Will it be necessary to carry out a Caesarian section, perhaps with no other hope than delivering a stillborn child?

Let us study the question succinctly, having no fear of the gibes of fools and ultramodernists. Only one artistic formula merits our regrets—I mean Romanticism. With it disappeared magnificence of expression, the hatred of compromise and the execration of vulgar sentiments, and it is not even in dry, laborious and affected Flaubert that it is necessary to go in search of what the Bousingots2 will bear into the tomb. The three blows of the golden hammer that “Père Hugo” struck upon the icy forehead of Classicism, slain by him, were followed up by Naturalism with the hiccups of the undertaker’s mute Bazouge3 in order to bury Romanticism in its turn. Impotent to emerge from the sewer of its conceptions, amorously licking its lips over the pus without succeeding in stating the causes of the infection, Naturalism, devoid of criticism, philosophy or any other esthetic than that of evening courses—if one excepts the author of Salammbô—has produced nothing that can resist Time. Also defunct in the prime of life, the concession of five years that it occupied in the cemetery of Parnassus did not take long to be attributed to Symbolism, a young hermaphrodite with the eyes of Lohengrin, which died of congenital scrofula, premature senility and unnatural habits.

Rest in peace the ashes of the dead. The old modalities of literature no longer square with modern aspirations, which require, first of all, research and analysis, no longer of surfaces but in depth. But in that consideration, can one not borrow from Romanticism what it created of the indestructible, and remove from Naturalism the narrow imitation of life that it was able to impose, in order thus to create a romantico-realist art?

We cannot, in fact, return to Classicism—“the source of beauty and harmony”—as many people recommend and strive to do. The road has fortunately been cut that would permit Letters to retreat into that museum of fossils and thus recover the conventions of Classicism—which is to say, to interpret excessive situations in measured terms.

The famous Locusta

Has redoubled her officious cares for me,

Causing a slave to expire before my eyes.

………………………………………...

Of poisoning, do you fear the blackness?4

It is evident that the exclusive concern for Virgilian grace and form caused Racine to by-pass reality and sincerity, and forsake the veritable restitution of the states of the soul to his characters, who trill musical verses while recounting unspeakable sins. His language is not and cannot be the language of human beings. There is a convention in it, a preoccupation not with truth but merely elegant expression, which is less acceptable than the excesses, relativities, incomprehensions and hysterias of ulterior Schools.

For writers worthy of the name, for those enfevered, tormented, driven to desperation and recomforted by their art, what remains to be attempted, in despair of a cause? Perhaps this: to get rid of the animal sentiment of Nature that Rousseau inflicted on French mentality, and which presently creates our entire sensibility: that exclusive love of the moon, little birds, stars, cool shade, murmuring springs; that systematic adoration of visible Nature, which intoxicates us with its plasticity in order more effectively to hide its soul, making humans resemble grazing ruminants, devoid of any understanding, in the pastures of the Earth.

The great problem of Equality, of social harmony, is nothing but this: can a thinking being believe that intelligence will ever succeed in annihilating instinct and subordinating profound human urges to the collective interest of social groups? Who can affirm that without imposture?

Instead of continuing, however, to be degenerate Greeks and Latin minus habentes,5 instead of continuing to delight in the bucolicism of primitive peoples, would it not be better to accord our literature with what we know of the laws of the Universe and prescribe a newer kind of sensibility. Would it not be possible to transfer from one generation to another the incoercible will to innovate? Could one not take possession of the positive conquests of the last century and simultaneously launch forth in pursuit of everything that constitutes color, originality, invention, the unexpected and the picturesque? Would it not be appropriate, first of all, to renew lyricism, presently disreputable; should it not be necessary to study profound causes as sources of ideology and thus give Letters what they have always lacked—which is to say, an inflexible scientific rigor in its observations and inductions?

I appeal to all novelists who have not annulled their self-respect. Should one not evacuate courageously the Galilean toxin that makes us accept the permanence of dolor as the only and indisputable attribute of the human race? Ought we not to return to the splendid immodesty of Latinity to study, other than in a spirit of lewdness, the anguishing question of Sex? Should we not undertake that which has not yet been done: conduct a vast investigation into the very essence of the World, as well as the true character of facts; an inquiry that will not depart from any a priori, nor take account of any dogma, and finally dismiss the benevolence of Nature with regard to Humankind? There, alone, resides salvation and there, I hope, a few pure artists might be encountered to save moribund literature, to open a vein in order to transfuse their generous blood to our pale and plaintive Idol, which dies a little more every day beneath the fetid breath of pedants and the victorious embrace of the asinine!

If the reader is astonished that events five thousand years distant can be conjectured with precision, it will be necessary for me to advise him that Monsieur Eliphas—a friend I have mentioned many times in my preceding books6—has concocted a substance whose ingestion permits the mind’s eye to plunge into the future.

Everyone had seen an arithmometer—a calculating machine—in operation. It is sufficient to line up the numbers and then turn the handle two or three times to obtain the total, the quotient or the product. Well, it is the same with the magic ingredient whose formula Monsieur Eliphas has devised, and which, without any possible error, bring about a rigorous perception of the future. Once the givens of the human or social problem have been set in the intellect, one swallows two or three pills of the blue-tinted paste. Immediately, the mysterious combinations of logic establish an understanding, and the solution is offered, of its own accord, on awakening, in all the triumphant glare of evidence.

A hundred times already, on my own behalf and that of others, I have been able to verify infallibly the diagnoses and oracular previsions due to the miraculous substance. When I emerged from the dream that had elucidated all enigmas for me, however, still under the influence of an entirely understandable amazement, and I asked Monsieur Eliphas to give me his secret immediately, in order that my fellows might have the benefit of it, he shook his head negatively and replied, angrily that “people don’t deserve to become intelligent.”

F.K.

Chapter I

The sixth month of the year 6905 had been reached.

That morning, Sagax, put in charge by his brothers of the repopulation of the City—Sagax, the Creator of Humans—was striding back and forth in the Artificial Fertilization Laboratory.

Above his head, copper tubes the color of red grapes snaked and intersected, like capricious creepers. Giant nozzles in which irascible gases snored rendered the rumbling menace of enslaved forces audible along the walls. Enormous paddles rotated of their own accord in fantastic jars. Into monstrous vats filled with boiling liquids, clad in of a metal akin to aluminum but transparent, little cables dipped that had the task of channeling compressed heat, transporting it over a distance like electrical energy. Gigantic retorts, around which dozens of slender test-tubes huddled, like an anxious broods around their mother, and multiple frail round-bottomed flasks displayed their pale bulbs in the background, while brass threads were entangled like giant spider-webs.

Through one of the bays of the immense hall, a cracked and valetudinarian sun was visible, a cheesy disk bordered in black, climbing slowly toward the zenith, wobbling in a yellow robe of greasy rays. On tablets of p

ure gold within arm’s reach, or imprisoned in platinum cupboards, a compact regiment of labeled phials, and enormous quantity of bottles, tubes and flasks were arranged in a long band—and all those recipients contained cultures of carefully-selected spermatozoids...

Four thousand years before, humans had escaped from the previously-accepted Norm, having understood that it was monstrous to continue at the whim of instinct, like animals, with no other regulation than sexual appetite, without being forearmed against the accidents of heredity, physiological and mental fatalities, baneful atavism and the terrible risks that the amoral and tyrannical Will of Nature imposes.

In the midst of the ruins of the old World, after the Great Cataclysm, a superior civilization had therefore blossomed.

Paradoxical as the fact might appear, the human species had become tolerant. The genius of the individual had subjugated the genius of the species. Thinkers had carried out an analysis of the generative act that gave birth in darkness, which, without any foresight, created a being in the gulf of happiness in which vertiginous flesh overwhelmed intelligence and imposed self-alienation.

The scientific method, the origins of which were lost in the night of time, and which had assured, in spite of everything, the perpetuation of the thinking race, was quite simple, to all appearances. It consisted, by surgical means, of removing from a specimen perfect in comprehension, knowledge and plastic beauty a few animalcules contained in his seminal liquid.

Love in 5000 Years

Love in 5000 Years