- Home

- Fernand Kolney

Love in 5000 Years Page 3

Love in 5000 Years Read online

Page 3

These vibrions, subsequently treated as virulent broths were once treated, served to fecundate the Reproductresses, themselves issued from a faultless line. Shortly after puberty, by means of a painless operation, one removed from the procreative subject—provided that he was exempt from any moral or physical fault—that which had been decanted from his predecessors; after which he was devirilized, or, to put it better, his sacred vesicles were desiccated with the aid of sterilizing rays.

The efficacy of these cultures was carefully maintained, and no week went by when Sagax did not stir, filter and decant them. Often, he even carried out separations and intermixtures. Those who had preceded him in his duty had scrupulously studied the flaws that might still remain in individuals, and, tracing them back to their causes—which is to say, the imperfection of certain ill-purified but clarified elixirs—they had repaired those errors of detail without difficulty.

The Great Work, the inheritance that Sagax had taken on, charged with the duty of preventing any deterioration, was therefore impeccable. The formulas of the fertilizers that produced Perfected humankind—humankind freed from the dementias of Sex—were, in fact, established and fixed forever. Over the centuries, Science had elaborated the gelatins that had finally hatched a Humankind orientated toward the sole joys of Lucidity and Knowledge.

Sagax was tall and well-built, with the musculature of a colossus whose slimness would have been maintained by games and combats. He had white skin, the curdled-milk epidermis of the ancient races that had lived in the North. His thick hair, bronzed chestnut in color, was reminiscent of the hue of sun-dried seaweed, and crowned a wrinkle-free forehead. He had attained the full expansion of his form, arriving at the apogee of youth. He was a hundred and ten years old.

He sat down on his work-stool and conjectured that the time had come for lunch. As he was reluctant to displace himself, he pressed a button. A flexible tube emerged from the wall, presenting at its extremity a cupel surrounded by perfumed vapor. With a contented smile, Sagax received the nourishment provided by the sterilizing apparatus.

Slowly, he chewed the little triangle of brown paste that contained, in compression, the appropriate quantities of nitrogen, oxygen, phosphate and hydrocarbon necessary to the alimentation of the human organism. His palate, expanding all of its papillae, delighted in the taste of the complete aliment. A material felicity prostrated him, blissful and ecstatic, in gustatory enjoyments certainly unknown to the finest gourmets of past societies.

Standing up now, his flesh lightened, his brain traversed by vivifying waves, he was about to review the bottles for the Action that that he was about to carry out that very day.

With a measured step, he filed past the sparkling golden shelves on which, dipped into water-baths at 37°, the ten thousand recipients were lined up that were destined to gratify with existence the simple citizens, the multitude without special provision, to whom only a mediocre talent would be dispensed. Those were the Elect, the ones who would savor the joys of life in all their plenitude, since they were exonerated in advance from the terrors of superior investigation.

Half of the labeled phials would engender males, the other half females, and they were further subdivided by category, each having the task of unfailingly procreating a type determined in advance, in order to maintain the fortunate diversity of human beings. Above them, preserved from any contact with the vulgar, was a sort of niche decorated with bizarre fabrics, where languid and versatile flames played, the supple and undulating reflections of metallic tissues that appeared to be woven with the luminous fibers of a rainbow.

There were enthroned the white magmas that contained, in potential, the Superhumans.

That special sumptuousness, that ennobling of function by eye-catching attributes—that sin against rigorous equality, in a word—had been planned by Sagax, who willingly made concessions to the joys of the retina in spite of the recriminations of the Sages, his colleagues.

On the bottom shelf, three or four slender flasks, whose cylindrical necks were swollen by protrusions, contained future mathematicians, those who would endow Space and bodies with the prison of formulae. Next to them, a flask in continual fermentation, with a tormented abdomen, marked with the figure 1,312 gave hospitality to the poets and prose-mongers of the future, and their seeds already seemed to be undervaluing one another and engaging in bitter combat. To their right was the famous bottle 8,703, which infallibly yielded philosophers, who had removed the somniferous power from Metaphysics and rendered Substance, Matter and Entelechy intelligible. Beside that, bottle 7,608 furnished athletes who realized the triumph of plasticity and revealed the unfailing harmony of the Universe by way of human harmony.

Higher up than all of those, looming over them by a cubit and resting on a nacarat dust-cover, the prestigious 4,245 was displayed, full of a liquid the color of cornelian. That one engendered the Physiologists for whom Nature had no coquetry, no spit and no secrets.

Sagax was himself the issue of that bottle of Porphyrogenetes.7 Pausing momentarily, he took hold of it with respectful and tremulous fingers and considered it lovingly. “Father!” he said, full of affection and veneration.

Often, by means of thought, he had wanted to evoke his ancestors, all those from whom he had emerged by scientific and rational fecundation, but who could ever succeed in establishing the pedigree, the lineage, of the zoosperms contained in the bottle that had put him into the world?

Sagax did not even know the patronymic of the person who had preceded him in his responsibility, for the present Civilization was liberated from all excessive gratitude toward individuals living or dead. Respect was commanded by character and not by function. Genius appeared as a banal matter of fact, since it was fomented by human will and no longer obtained by hazard.

Did the people who paved the streets and this prevented citizens from spraining ankles deserve less gratitude than the writers who taught them to reason correctly and frame rigorous deductions within one another, thus avoiding mental sprains?

Everyone accomplished his task without expectation of moral or material reward, solely for the pleasure of being useful, virtuous and noble—and humans, having become just, no longer wanted to be supervised by the brains of the past. In their march toward the future, their ever-more-precipitate race toward incessant progress, they were unwilling to allow themselves to be held back by clawed hands from beyond the grave.

Sagax’s colleague, Thales, the Grand Pedagogue, had a theory about that. By virtue of dismantling and reassembling the mechanism of human intelligence, he had arrived at the declaration that, in the Civilizations of Prehistory, the Past had always dominated the present—but that was only a pure hypothesis in the eyes of the Grand Physiologist. How could it have been the case that abusive determinants, an aged intelligence, had served as motors of entirely new organizations and collectivities, of which the defunct ideologues had been unable to know either the needs or aspirations?

The only certainty that Sagax could have relative to the advent of the Age of Civilization was that of the Great Upheaval.

One day, as if all the heavenly bodies had acted in concert, the globe had been suddenly battered, like an egg in a snowstorm, by frightful discharges of magnetism. The Cosmos, seized by delirium, had attempted to shake everything up in a supreme convulsion. Swirls and whorls of frantic fluids, an enveloping network of electrical typhoons, had unexpectedly wrapped the planet in an unbreakable straitjacket of force. The framework of the senile spheroid had cracked, a howl of agony had emerged from its bosom, and a frightful dysentery had caused its faeces to expand through the open outlets of three thousand resuscitated volcanoes. Like green-tinted vomit ejaculated by dead-drunk Nature, the boiling Mediterranean and the Atlantic had squirted over the Occident, in order to abolish it forever.

The servile moon, which had previously displayed the erysipelas of its stupid face sufficiently in the cloud-patched sky, had been swept away like an item of detritus and, whimpering like

a lost dog, had launched forth into the void in search of a new master. Rejected everywhere, it had come back, imploring, offering once again to its suzerain the assistance of its domesticity for nocturnal lighting. Crumpled and dried up, like a eunuch’s scrotum, it was already clinging on to its accustomed place when, whipped up by a fabulous wind, the Sun had started setting Space ablaze, licking the neighboring constellations craftily with a tongue of devastation, from which a furnace of saliva ran. Then, in the hope that it might be allowed to live in spite of everything, the Earth had made itself very small, dancing on the waves of the ether like a shriveled piece of filth on the crests of the swell.

Such was the Tradition. Certainly, as with everything that humans consigned by means of memory, there must have been a great deal of exaggeration in that version of the inconceivable events, which no writing had recorded. Sagax was not unaware that the vertically-locomotive bipeds had never been able to obtain an identical consciousness of a fact realized before them; he knew that, even by the next day, there would always be a hundred contradictory accounts. That was a fault of human mentality which he had never been able to correct, even among the contemporary Perfected, even though he had brought the spermatozoids to the apogee of Finitude.

But what was extraordinary, after all, about the fact that humankind was unable to determine the causes of the disaster? Can the parasites and mites that take advantage of a fetid body conceive the reason for a slight somersault that might crush half of them? They never attribute the cause to the itch they produce, and are obliged to consider themselves as victims. It was not a paradox to say that the explanation of the unseasonable minuet sketched by the Earth in the absence of any congruous gravitation might perhaps be of the same sort.

Whatever the reason, the Cataclysm was undeniable. Was it necessary to attribute it to the disorbitation of a sphere in the solar system, which, in a fit of bad temper, had started wandering outside its accustomed parabola? Or should one put faith in an inscription found on a monolith more than four thousand years old? Traced in characters identical to those currently in use, couched in a language that was still alive, that epigraph stated, with an ironic and trivial lyricism:

Only a comet, one of those diamante-decked whores clad in lacy light with luxuriant manes, which they fluff up in space, could have thrown herself in that way into the midst of a family of seven planets. Gripped by an infatuation for the Sun, the superb male, she must have begged him to set up home with her, to be her lover of the heart.8

But what did the words whore and infatuation, and the phrases fluff up and lover of the heart, signify? Sagax promised himself that he would explain, one day, that caprice and that reaction of Matter, even though nothing remained of the primitive Ages—not one book, coin or peremptory document—and that between present Civilization and the Past, a vast gulf was hollowed out, a gigantic ditch that perhaps no one would ever bridge.

But bottle 4,245 had put him into the world to know everything; thus, he swore that he would not die before having reckoned with the mystery that he found particularly tormenting.

The previous year, a problem—of lesser importance it is true, not being forbidden—had capitulated to his perspicacity. For a long time, a few individuals in the Fraternal City had expressed a disconcerting opinion, declaring that humans had not always reproduced as in the present epoch. Legend accredited the rumor that they must once have gone about it by barbaric means, like the inferior species. Sagax, who did not like legends, had not had any difficulty in demonstrating the absurdity of that one. His rigorous controversy and scientific argument had put paid to it, without any possible recourse.

Suddenly, an unexpected anguish sent icy waves through Sagax’s arteries. Having reached the heights of Knowledge, would he ever attain the supreme Summit, the miraculous Peak where the source of Causality hides?

With regard to one difficulty that none of his predecessors had been able to overcome, however, he had triumphed. He had immunized the spermatozoa that would later become humans against every possible malady of life. Thus, he had freed humankind from physical disorders and annihilated the evil force that had previously caused the heart of the World to beat faster.

On the other hand, realizing the transformation of simple substances, manufacturing precious stones by the cartload was child’s play to him. Furthermore, he thought he was on the point of obviating a major fault in the human mind; he thought he would be able, before long, to understand “things in themselves.” And yet the master key of his intelligence was still impotent to pick, as it were, the locks of one slight enigma.

Yes, he wondered, why had culture 1,758, until then affected to beget flawless thinkers, suddenly engendered a subject who, when scarcely twenty years old, had fallen into irreducible stupidity, definitive occlusion and incurable cretinism? Horror! He could still see the imbecile it had perpetrated: the forehead bulging like a mature marrow, eyes of viscous porcelain, the face of a fetus beneath the temporal lobes of a titan, the lower jaw incessantly beating the muscles of the neck, mucilaginous jujubes in the corners of the lips, a pear-shaped abdomen supported by legs that would easily have fit into the skin of an eel, moving amid the disgust and terror of his siblings.

A shrill plaint suddenly molested the silence of the Artificial Fertilization Laboratory. Although that weakness was unworthy of a scientist, Sagax, his mouth wide open, gave voice to his lamentations. With his hand on his epigastrum, as if the drill of remorse were sinking into his chest, he moaned in bewildered contrition. What was the malfunction of culture 1,758 compared with the failure of bottle 1,324? That one, for a hundred generations, had produced moralists who, before the marveling eyes of their contemporaries, spread the supreme splendors of souls with facets of diamond, Sages who had conquered previously-inaccessible treasures of psychic beauty, and Ideologists who had caused quivering enlightenment to rain down upon their fellows, the dew of comfort deducted from the purest constellations of the mind. Well, 1,324 had authored a real rascal!

It had elaborated an individual named Phegor,9 whose vice could not be catalogued, for the terminology in use had not anticipated such a case. One particularity initially attracted attention: he had been born with a blemish over the right eye.

As if he wanted to redeem that congenital infirmity, without any known precedent, he manifested excessive good manners and bright smiles and luminous urbanity, perennially hoisting the great flag of eloquence upon the flow of an inexhaustible verbosity. Flexible in his backbone, that obsequious biped snaked along the ground at the slightest apparition of another person. From his throat emerged, effortlessly, girandoles of compliments and festoons of madrigals, with which he beribboned his interlocutor while his feverish rump sketched a mazurka full of invitation. Then, when he had captured the good will of his opposite number in the insidious net of attentions and immoderate praise, his voice, greased with the Vaseline of hypocrisies, promised exceptional felicities and his impatient fingers strayed toward the partner’s lower abdomen...

One morning, Sagax had nearly been knocked over by him, and he thought that a puerile desire to play leap-frog had suddenly gripped the other—but immediately afterwards, the Grand Physiologist, the Creator of Humans, had been constrained to employ force to avoid incomprehensible titillations.

Sagax had seen dogs in the City behave in the same way.

Why, why, in imitation of bottle 1,758, which had engendered an imbecile instead of a scintillating thinker, had culture 1,324, which should have given rise to Moralists, lead to the birth of a bimane whose primary concern was to manifest canine turpitudes? How could that sidestep into the absurd and unexpected ever be explained?

And Sagax, who knew that he was responsible, uttered another groan like an organ-pipe, unleashing a high note of desolation. How could he be unaware, in fact, that since those inauspicious days, his brothers no longer looked at him with expressions softened by gratitude, and that eyes illuminated by joy no longer followed him, as before, to approve his

genius, while he wandered through the City of harmony, solitary and pensive?

Nevertheless, he calmed down, and went to consult a chronometer in perpetual movement. As he approached the transparent wall he saw a gigantic figure, the number 2, rise into the air like a condor in search of the wind, soar for a minute, jostle other signs, and then come to a halt, horizontally, in a black crackling fulguration. Shortly afterwards, a smaller streak beside it indicated the elapsed minute. The clock of the last human colony that persisted in living on the planet marked the hour.

Then Sagax got busy, for the moment was nigh. He armed himself with a golden syringe—the dosimetric syringe that gave Life. Full of unction, gripped by a sacred emotion, his fingers trembling with filial respect, he took possession of his author: the 4,245, whose produce the Reproductress Formosa10 was to receive, and thus perpetuate his brother, the individual who would one day replace him in the heavy duty that he had assumed.

Sagax emerged from the Artificial Fertilization Laboratory and odorous air, its nitrogen diminished by triumphant chemistry, lashed his face, driving delights into his bosom, inflating his veins with a reinvigorated blood laden with optimism. In front of him extended the geometry of vast building, in which he reigned with his colleague Mathesis,11 the Prefect of Machines. To the left, in an immense hall, furry humans devoid of any garment but the coarse or silky, curly or wooly hair that covered their bodies, occasionally pulled a lever or turned a handle, precipitating the haste of pistons and wheels—for simple mortals, thus naked, had repudiated the vestments that differentiated the castes in primitive humankind.

Many of these workers were decked as if with seaweed, others fleeced like the caprine race; a few were loosely clad in the woody fibers of tawny manes; some seemed to have woven breeches and doublets with the rutilant tails of chestnut stallions. Many, angoras, trod on their long silks—and Sagax noticed that those had neglected to have themselves clipped, as he had advised them to do.

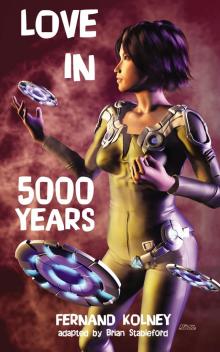

Love in 5000 Years

Love in 5000 Years